There’s a cutting irony involved in bringing a bevy of environmental justice scholars together in real time every two years. Not only do conference preparations depend on carbon-intensive practices like flying, but they often materially support the convention centers and tourist economies that dispossess the city’s poorest residents. That reality was not lost on Nicole Seymour, an English professor at Cal State Fullerton who serves as Co-President of the Association for the Study of Literature and the Environment (ASLE). This was in fact why Seymour wanted a keynote speaker like Kaia Sand. In 2023, ASLE held its biennial gathering at the Portland Convention Center, which brought conference attendees into intimate contact with the city’s homelessness crisis. Seymour wanted someone to speak at the Association’s 2025 gathering, held this past July at the University of Maryland at College Park, who could address the specifically environmental inequities of homelessness.

A poet, journalist, and artist whose work bridges scholarly research, creative practice, and experiential knowledge, Sand was for seven years the executive director of Street Roots, an alternative newsweekly and organization that advocates for unhoused communities in Portland and beyond. There, she helped bring unhoused folks into research and policy, humanizing the many structural inequities that drive homelessness while archiving the knowledge, stories, and creativity of unhoused people to better inform policy. After the health impacts of this work forced her to step back in late 2024, she launched Unwanted Persons, a book project (and website) that focused her advocacy work to writing by compiling dispatches from the frontlines of alternative first responder programs around the country.

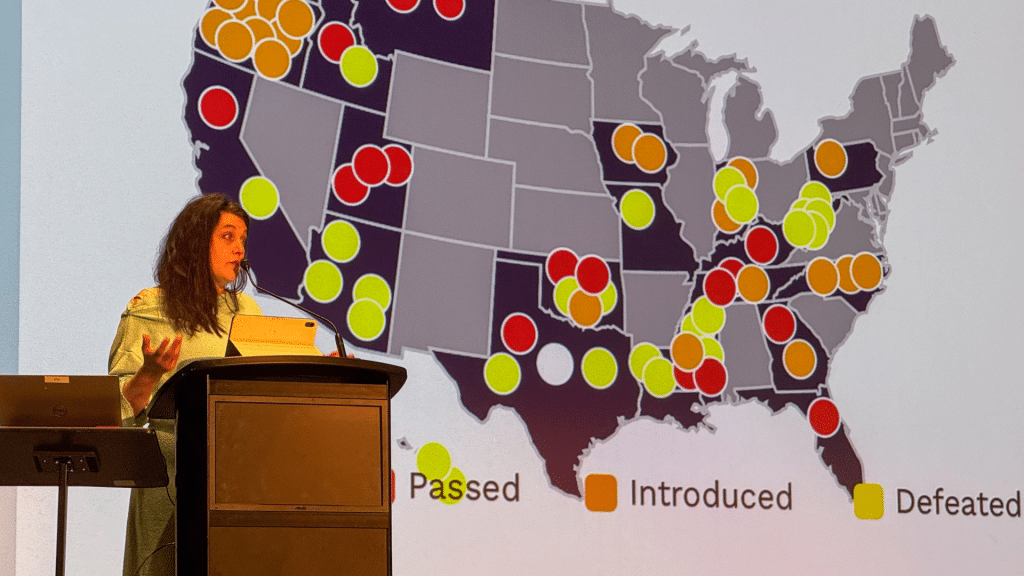

Sand’s keynote for ASLE presented some of this project, in particular the historical context and contemporary policy landscape for constructing those lacking adequate housing as “outlaw, unwanted people, which is a common police code in cities—‘unwanted person.’” Through criminal code, policy, Supreme Court rulings, hostile architecture, and 911 as a system that leads to overpolicing rather than provision of care, Sand detailed how “our systems actually render that [disposability], they actually make that happen.

“Even though we’re corporeal, [unhoused people] are constructed in such a way that somehow their corporeal self is not supposed to exist anywhere,” Sand said.

Even systems for making homelessness visible routinely invisibilize the extent of the crisis. Referencing Brian Goldstone’s There Is No Place for Us, Sand pointed out that the annual Point in Time counts tally only those who sleep on the streets or in shelters (around 750,000 in 2025), excluding people experiencing invisible forms of homelessness, like “doubling up” with friends or family or living in homes that lack electricity or running water. Including people in these situations brings national counts closer to an estimated 4-5 million people, according to Goldstone.

Sand’s keynote addressed some of the systemic causes for these numbers, which have also produced their heavily racialized character. At root is the cost of housing, which far exceeds the income of those working for minimum wage or engaging in the informal economy (Uber, Door Dash, etc). This only exacerbates the lack of generational wealth among Black, Indigenous, and other peoples of color as a result of historical dispossession and displacement—from colonial legacies of land theft and broken treaties for Indigenous people to redlining and the subprime mortgage crisis for Black communities.

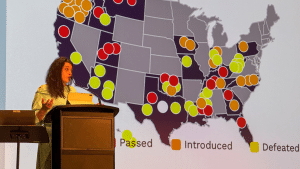

Increasingly, states and local governments have responded to this crisis by criminalizing homelessness, a development facilitated by the Johnson vs Grants Pass, Oregon decision handed down by the Supreme Court in June 2024. Previous precedent established by the 9th Circuit held that arresting or citing people for sleeping outdoors when no real alternative existed constituted cruel and unusual punishment. Grants Pass, however, “opened the flood gates” for cities and states to pass anti-camping and other anti-homeless policies, Sand said.

Much of this “copy, paste, incarcerate” legislation has been pushed by far-right think tanks like the Cicero Institute, headed by Texas billionaire Joe Lonsdale, a friend of techno-fascists Elon Musk, JD Vance, and Peter Thiel (the latter of whom co-founded law enforcement surveillance company Palantir Technologies with Lonsdale). The desire of Silicon Valley elites to see the unhoused people outside their headquarters rounded up and disposed of has only been turbocharged by Trump’s most recent executive order, “Ending Crime and Disorder on America’s Streets.” This expansion of mass incarceration as a response to homelessness over housing and healthcare has already borne fruit on the streets of DC, with Trump using “drugged out maniacs and homeless people” as one pretext to effectively occupy the District, seizing control of local police and dispatching the National Guard to “do whatever the hell they want.” As of August 13, encampment sweeps have begun in DC, starting with Trump’s routes to the golf course and Kennedy Center.

Climate-linked disasters are also a major driver of homelessness, Sand said.

“I would add to that the climate disasters of our time: fires, floods, hurricanes. Every [disaster] there’s going to be people that … lose their land and are not able to rebuild.” As we have seen in San Antonio in the deaths of Albert Garcia and Jessica Witzel, “people who are [living] outside and homeless are on the frontlines of the climate disaster.”

And yet Sand, as a poet, was equally concerned with how “creativity persists under incredibly harsh conditions.” Peppered with photographs from cities around the world, from Portland, Oregon to Paris, France—where a large proportion of unhoused people are immigrants from former French colonies, the product of a dual criminalization, migration and homelessness both—her presentation also documented the resourcefulness and beauty of “the workaround.”

“I love that [despite] all this hostile architecture, people find a way,” she said. “This [photograph] is a tent, they made a platform on the rocks. I’ve seen where they’ll put flowerpots out and people use that to create a foundation.”

Sand also detailed how attention to creativity prescribed a three-dimensional methodology, moving her poetic thinking off the page and into “organizing and journalism” in an effort to imagine, enact, and archive alternatives to the largest-scale systems of harm. On discovering that half of all arrests in Oregon are of unhoused people, and that 911 received an “unwanted person” call every 15 minutes, Sand began sitting in on 911 calls and realized that, outside of medical emergencies, operators largely had no resources to offer callers, dispatching police by default in what Sand described as “carework through violence.” Historical research further revealed the racist origins of 911, created in Alabama in 1968 as backlash to the 1967 Kerner Report, which pushed for investment in Black communities to address civil unrest—but also a single number to activate police response.

The focus of Sand’s project, then, became: “How does care function on the 911 line? How do we create out of this destructive circumstance?” Modeled after CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out on the Streets), the groundbreaking crisis intervention team in Eugene, Oregon, Sand and Street Roots launched Portland Street Response in 2020, responding in part to the murder of George Floyd, which greatly amplified nationwide calls for alternative first responder systems. By 2025, 130 of these programs have launched across the United States—“it’s kind of the opposite of the map I showed with all the [anti-homelessness] laws,” Sand observed. Some programs, such as Albuquerque’s Department of Community Safety, are co-equal to police and fire; others, as in Dayton, Ohio, dispatch “field mediators” to resolve conflicts arising from isolation or lack of resources.

What alternative first response can offer is care through de-escalation, but also the time it takes to “listen to the story beneath the story … as much time as [people in crisis] need.” Here, Sand presented the story of a man on whom a 7-11 worker had called 911, which via CAHOOTS dispatched a crisis worker and medic rather than police. After spending time treating the man’s wound and talking to him, crisis workers learned he also had cancer and no way to get to an upcoming doctor’s appointment, which had led him to become emotionally overwhelmed. They were able to de-escalate him, but also took the man to his doctor’s appointment. As Sand said, this was “care without violence.”

In San Antonio, we have seen firsthand the difference it makes, as in the case of unhoused neighbors like Albert Garcia, to be able to call on community careworkers like Yanawana Herbolarios.

For Sand’s part, her project is “to take my poetic, journalistic brain and go around the country” archiving these alternatives.

“I write dispatches, I go on first responder rides, and I try to keep learning … more about how care can work, and more about our society and what’s broken.”