This article originally appeared in Insider NJ.

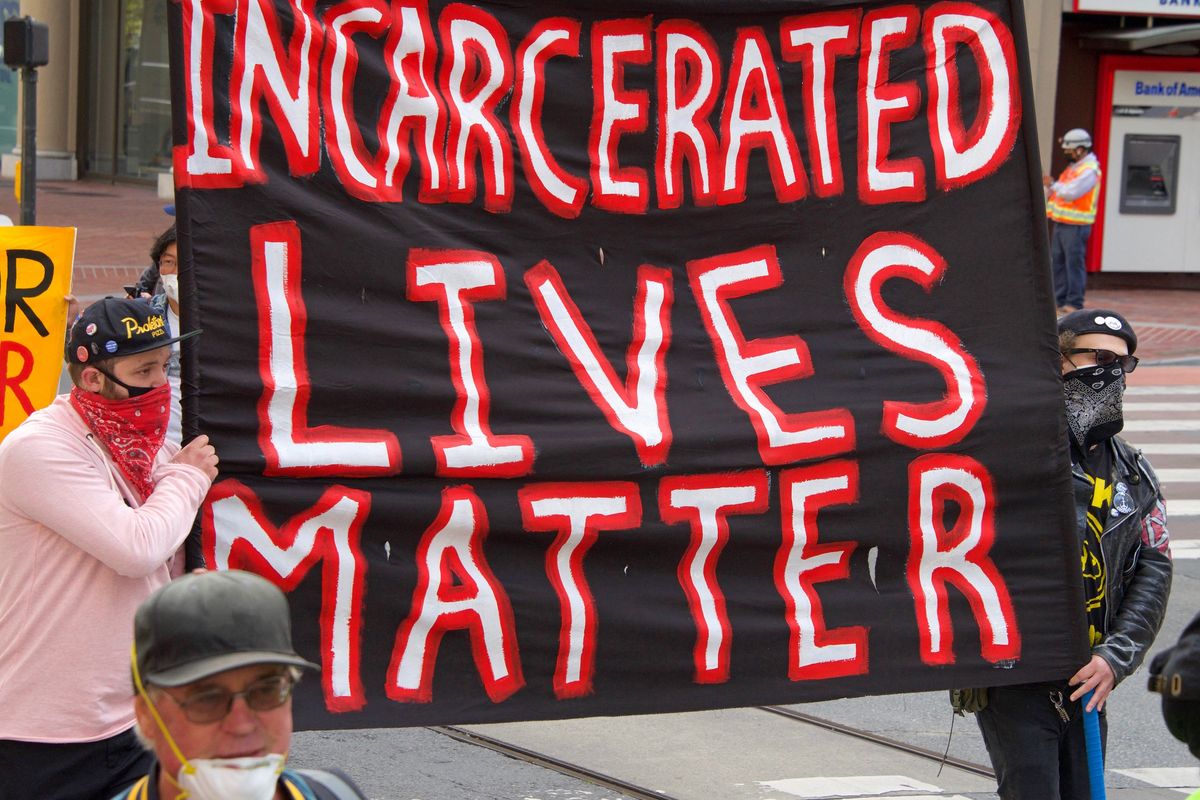

As we celebrate Juneteenth, we should reflect on the reality that the abomination of slavery is not entirely in our collective rear view mirror.

It endures.

The United States is still having real trouble giving up its addiction and reliance on involuntary servitude, a.k.a slavery. Like the free land we extracted from the Native Americans, it’s a footing of the foundation of our great pyramid that still stands in the 21st century.

Consider that in 1865, even as Congress was enacting the 13th Amendment to the Constitution to abolish slavery, it created a loophole that it would remain legal as a punishment “within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the former Confederate states used the pretext of minor crimes, like loitering or vagrancy, codified in law as the “Black Codes” to imprison thousands of Black residents who were in turn leased out to plantations. The use of the 13th Amendment loophole became so common that by 1898, close to three-quarters of Alabama’s state revenue was generated by renting out Black Americans.

Here in the U.S., which is 4 percent of the world’s population, we have 16 percent of the planet’s incarcerated persons, according to the Vera Institute, a social justice non-profit. The American justice system incarcerates close to two million people annually, overwhelmingly people of color that are mostly jailed for non-violent or drug-related crimes.

That’s just too large a captive labor pool to go unexploited in our punitive winner-take all system.

ALSO READ: Why do we use ‘cult’ to describe normal illiberal politics?

Last year, the American Civil Liberties Union reported that prison workers had produced close to $11 billion in goods and services but received “just pennies an hour in wages for their prison jobs,” according to the Guardian newspaper.

“Since the end of the Civil War the United States has had a deep and troubling history of extreme exploitation of prison labor — primarily of black, brown and poor convicts who are abused by corporations and local businesses,” said Joe Wilson, a noted labor historian and author. “This is well documented in the South as well as the North in the production of everything from furniture to license plates and includes their exploitation for stoop labor in agriculture as well as call center work.”

Wilson adds, that because prison labor earns “just paltry or no wages” it has the secondary impact of undermining the value of labor outside the prison walls “in the fields, factories and offices where they undercut wage workers.”

Last year, in an insightful story by the New Jersey Monitor’s Dana Diflippo readers learned of the plight of New Jersey inmates were getting paid a dollar or two a day at their prison jobs even as the “Department of Corrections, consequently, hiked prices in prison commissaries, the only place incarcerated people can buy basic necessities and food.”

“Prison justice advocates say the widening gulf between inmate wages and commissary prices reflects a culture of disregard that pervades many prisons,” reported the news outlet.

“Having someone work for $2 a day is essentially slave labor,” Jennifer Lewinski, a co-founder of the Asbury Park Transformative Justice Project, told the New Jersey Monitor. “There’s no humanity to it.”

“It makes people feel like their labor is worthless, like nothing they do has any value,” Ron Pierce, a former inmate who is now with the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice,” told the online news source. “And when you come home, you’re going to end up with a lower paying job — and you’re almost happy to accept it because you’re so used to making nothing.”

Pierce told the New Jersey Monitor, that over 30 years he was only able to save $208 when he left the state’s custody in 2016.

Under legislation being sponsored by Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ), Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-OR) and Rep. Nikema Williams (D-GA) the so-called 13th Amendment’s exception clause permitting slavery as punishment for crime would be closed.

“In 2023, we still have legal slavery in the United States because Congress left this institution in place for ‘punishment for a crime’ when it passed the Thirteenth Amendment,” Booker said in a statement. “This has allowed our government to exploit individuals who are incarcerated and to profit from their forced labor – perpetuating the oppression of Black Americans, mass incarceration, and systemic racism.”

Booker continued: “This loophole is at odds with our nation’s foundational principles of liberty, justice, and equality for all our people. It is time we pass the Abolition Amendment and finally end the morally reprehensible practice of slavery in this country. We must ensure that all people are treated with fairness and dignity to truly live up to our nation’s promise.”

“This country was founded on the principles of equality and justice — principles that have never been compatible with the horrific realities of slavery and white supremacy,” said Merkley. “Nearly 160 years after the 13th Amendment was ratified, the evil remnants of slavery persist in the U.S., embedded in the heart of our Constitution. To live up to our nation’s promise of justice for all, we must take a long overdue step towards those principles by removing the loophole in our ban on slavery. No slavery, no exceptions.”

“Slavery was wrong from day one, and we should have abolished it when the 13th Amendment was ratified,” said Rep. Williams. “I will keep pushing — no matter how long it takes — for Congress to close the Slavery Loophole in the Constitution, finally ending slavery in America once and for all.”

“Slavery is hidden behind prison walls, in a system rife with racial prejudice, abuse, and inadequate oversight — out of sight and mind as long as we may pretend people inside prison are not people. They are,” said Celina Chapin, Associate Director of Advocacy at the Anti-Recidivism Coalition. “Where slavery exists, community health, rehabilitation, justice, and true public safety cannot.

Last June, the University of Chicago Law School’s Global Human Rights Clinic teamed up with the ACLU to conduct the first of its kind national survey of the status of prison labor in the United States.

Researchers found that two-thirds of U.S. prisoners were working behind bars with over three quarters of those surveyed reporting they faced punishment “such as solitary confinement, denial of sentence reductions, or loss of family visitation — if they declined to work.”

In addition to being excluded from federal and state wage guarantees, prison workers told researchers they did not receive adequate training and safety equipment. As a consequence, 64 percent of incarcerated workers worried about their safety on the job.

According to Captive Labor: Exploitation of Incarcerated Workers “more than two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, during which incarcerated workers faced especially brutal working conditions” they were “denied early access to vaccines in 16 states” even as they were “forced to launder bed sheets and gowns from hospitals treating COVID patients, transport bodies and dig graves.”

“More than a third of incarcerated people have contracted COVID-19 since the pandemic started and more than 3,000 have died,” according to the national report released last June.

Consider the plight of California inmates who volunteered with the state’s Conservation Camp Program which fights wildfires.

Time magazine reported that “more than 1,000 inmate firefighters required hospital care between June 2013 and August 2018” and that they were “more than four times as likely, per capita, to incur object-induced injuries, such as cuts, bruises, dislocations, and fractures, compared with professional firefighters working on the same fires.”

Time reported that “inmates were also more than eight times as likely to be injured after inhaling smoke and particulates compared with other firefighters.”

Between February 2017 and February 2018, three California inmates with its Conservation Camp Program were killed on the job

“While the rate at which inmate firefighters experience certain injuries is higher, their pay is lower, compared to the full-time firefighters they work alongside,” recounted Time magazine. “Inmates make only $2 per day taking part in the Conservation Camp Program. During an active fire, which has them working 24-hour shifts, they make an additional $1 an hour.”