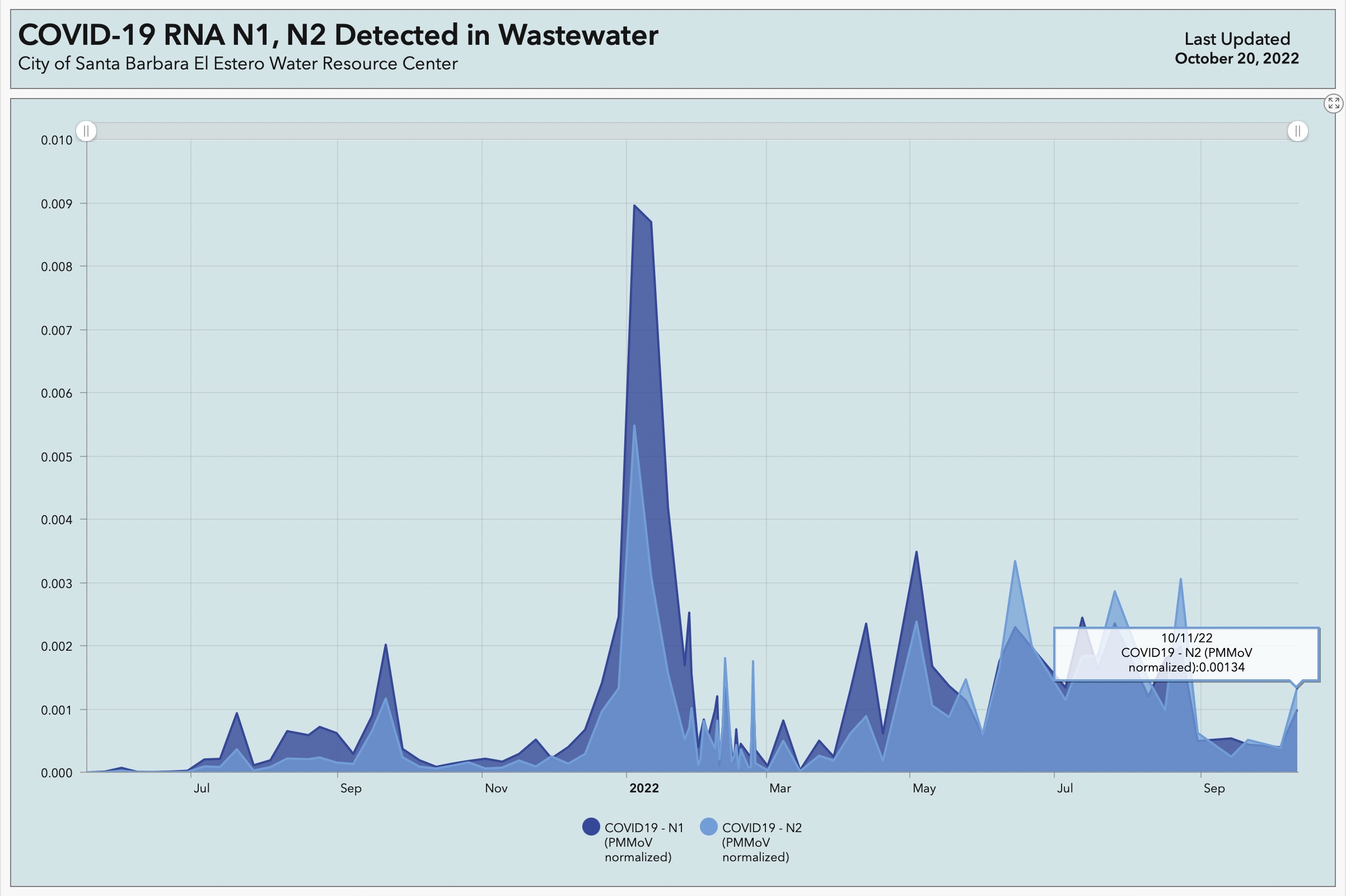

Now that so much testing for COVID-19 is done through home kits and cannot be officially tracked through lab reports, the presence of the virus in wastewater has become an important indicator of its presence in the Santa Barbara community.

Since the earliest days of the pandemic, the city’s wastewater division at El Estero Water Resource Center incorporated testing for the virus into its routine water-quality examinations, said Amanda Flesse, head of the wastewater system. “We’d been following the progress of the disease in China and Europe,” she said, “and in January 2020, a lot of European countries began testing their wastewater.” The City of Santa Barbara followed suit.

At first, Flesse’s team used a trial program that was available for free, but the results were not verifiable, she said, and they didn’t feel confident about distributing those numbers. By June or July, they’d found a verified lab in Florida the city could afford, and they’ve sent a composite sample across the country once a week ever since. Those results are now posted at a dashboard, but they also go for analysis to groups of medical doctors, researchers, and scientists at County Public Health, UC Santa Barbara, and Cottage Health, including Dr. Lynn Fitzgibbons, an expert in infectious diseases.

The most recently posted findings at the dashboard were edging upward. Fitzgibbons, who is not only generous with her time but also gifted with the ability to turn complicated scenarios into comprehensible words, was not too alarmed, yet. Looking at wastewater data California-wide, the trend was fairly flat: “One week is probably too little to tell us much,” she said. Locally and in most of California, the wastewater results were detecting RNA from the SARS-CoV-2 virus in general and not from specific variants.

Dr. Lynn Fitzgibbons, Infectious Disease specialist at Cottage Health. | Credit: Daniel Dreifuss (from file)

” data-medium-file=”https://www.independent.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200518-Fitzgibbons-02.jpg?fit=217%2C300″ data-large-file=”https://www.independent.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200518-Fitzgibbons-02.jpg?fit=741%2C1024″ loading=”lazy” src=”https://www.independent.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200518-Fitzgibbons-02.jpg?w=741&resize=312%2C431″ alt=”” class=”wp-image-268520″ width=”312″ height=”431″ srcset=”https://www.independent.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200518-Fitzgibbons-02.jpg?w=3000 3000w, https://www.independent.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200518-Fitzgibbons-02.jpg?w=217 217w, https://www.independent.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200518-Fitzgibbons-02.jpg?w=768 768w, https://www.independent.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200518-Fitzgibbons-02.jpg?w=741&resize=312%2C431 741w, https://www.independent.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200518-Fitzgibbons-02.jpg?w=1112 1112w, https://www.independent.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200518-Fitzgibbons-02.jpg?w=1482 1482w, https://www.independent.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200518-Fitzgibbons-02.jpg?w=600 600w, https://www.independent.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/20200518-Fitzgibbons-02.jpg?w=2000 2000w” sizes=”(max-width: 312px) 100vw, 312px” data-recalc-dims=”1″ />

Santa Barbara County remains in the CDC’s green tier for COVID-19 community levels, which is the lowest level. The weekly metric for case rate is estimated to be 43.67 per 100,000 population, and new COVID admissions to hospitals is at 3.8 per 100,000. As of October 27, in raw numbers from the state, 23 people were hospitalized in the county, four of them in the ICU, which have roughly been the case for about a month. The last reported death was apparently on October 7 (recent data is incomplete); a total of 729 county residents have lost their life to COVID since March 2020.

Asked about vaccines, boosters, and the new Omicron subvariants — BA.4 and BA.5 are old hat; the new kids on the block are BQ.1.1 and BF.7 — Fitzgibbons said the subvariants currently circulating are causing milder symptoms, which are more allergy-like and more in the upper respiratory system. People still come down with pneumonia, but it is a much less frequent outcome than when COVID-19 first hit.

Unfortunately, the new subvariants have also developed an increased ability to evade the immunities people have built up over the past three years. Fitzgibbons saw this to be the result predicted by virologists: The virus is adapting to infect more humans but at a lesser rate of mortality.

“As individuals and as a whole population, we now have this partial and complicated set of protections — or immunity — from previously being infected, previously being vaccinated or boosted, or even being infected a couple of times,” Dr. Fitzgibbons said. The available vaccines and boosters continue to protect from serious disease and hospitalization, she said, and create a good immune response. They work best within two to three months of injection, and anyone boosted last winter will benefit from another as the cold season approaches, she advised.

In Santa Barbara County, 12.1 percent of eligible people have gotten the new bivalent booster shot — now available to all ages 5 and up — compared to 11.4 percent in California and 7.3 percent across the U.S. More than 69 percent of those eligible in the county have at least the primary series of vaccinations.

The increased ability of the subvariants to elude antibodies might affect people with immune deficiencies the most. Many patients with cancer or other diseases are given monoclonal antibody transfusions as an extra layer of protection, Dr. Fitzgibbons explained, but some of the Omicron subvariants are able to evade those treatments. For many at the highest risk from opportunistic infections, wearing a mask for protection in crowded indoor places continues to be a precaution.

The wastewater surveillance testing costs the city about $15,000-$20,000 per year, said Flesse. The group that receives the information is hopeful that the program could be expanded to include other viruses of high concern, possibly through labs at UCSB. Dr. Fitzgibbons notes at the dashboard website that flu and other animal-host viruses, norovirus, hepatitis viruses, poliovirus, and multi-drug-resistant organisms are on the list of bugs they’d like to be able to detect from the wastewater stream.

They’ve learned from COVID-19 that the wastewater picks up viruses several days or a week before symptoms begin to show, said Flesse. “It gives us a really good idea of what’s in the city.”

Support the Santa Barbara Independent through a long-term or a single contribution.

The post Santa Barbara Continues Coronavirus Sewage Surveillance appeared first on The Santa Barbara Independent.