Ricardo Liniers Siri

” data-medium-file=”https://i0.wp.com/www.sevendaysvt.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Comics1-1.jpg?fit=300%2C214&ssl=1″ data-large-file=”https://i0.wp.com/www.sevendaysvt.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Comics1-1.jpg?fit=780%2C556&ssl=1″>

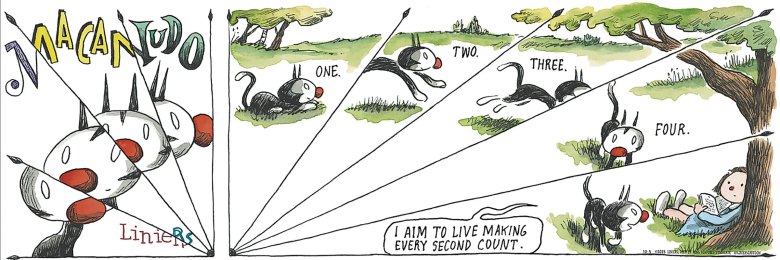

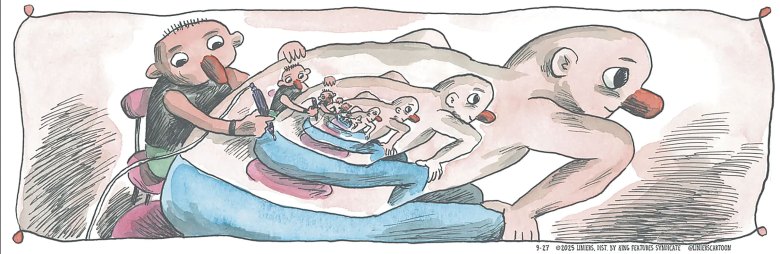

Remarkably little seems to happen in “Macanudo,” the daily comic strip created by Ricardo Liniers Siri, the Argentine cartoonist known professionally as Liniers. If you were forced to describe any given Liniers strip purely in terms of plot, you would end up saying things like: A ladybug lands. A man runs across a field with great purpose, then forgets what he wanted to say. An elf sings Van Morrison. Sometimes, it rains.

Liniers’ comics appear in newspapers in eight countries, including Brazil, Canada, India and Finland, and circulate in some 120 publications across the U.S.; he has also drawn covers for the New Yorker and written and illustrated nine books for children. Since 2016, he has produced his body of work from his home in the woods of Norwich, where he lives with his wife, Angelica del Campo, and their three daughters.

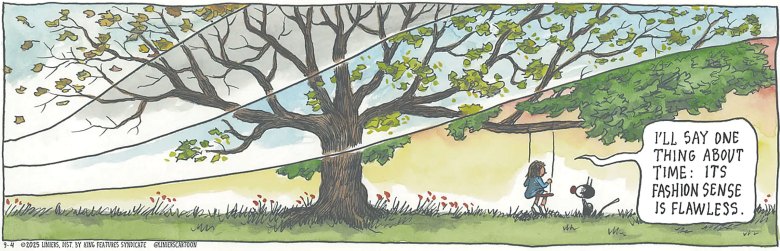

Liniers may live in the Upper Valley, but “Macanudo” is about life anywhere, because he doesn’t make the strip for people in Argentina or Vermont, or in any particular place. His work is an invitation to reflect upon the beauty and banality and weirdness of everyday existence. “Macanudo” — Argentine slang for “great,” as in “It’s all macanudo” — reflects Liniers’ insistently optimistic worldview in the face of unavoidable suffering and his gift for finding deeper truths in the most ordinary moments.

“He’s like some kind of holy fool,” James Sturm, director of the Center for Cartoon Studies in White River Junction, told me. “He’s sweet and playful, and yet he speaks fundamental truths.”

Readers in the U.S. can most easily read “Macanudo” on the website Comics Kingdom, which publishes the strip daily, as well as in more than a dozen collected volumes. What defines a Liniers cartoon is its playful exploration of the subtlest gradients of feeling, the darkness and light in the human condition.

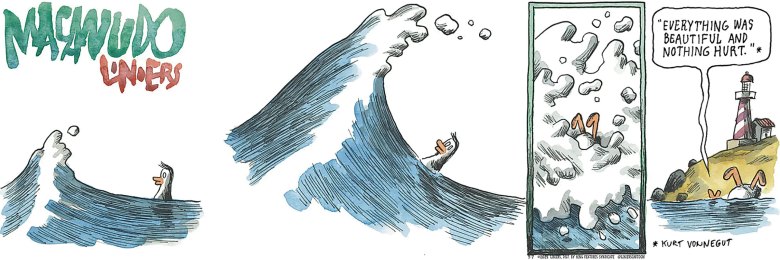

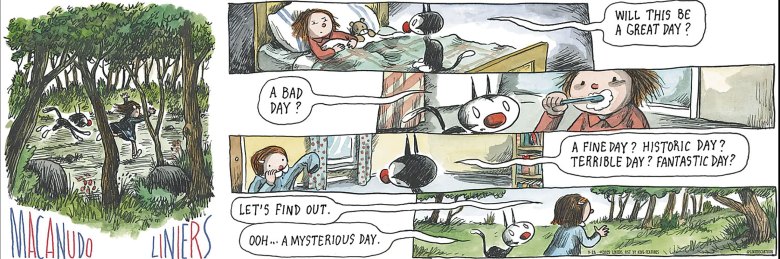

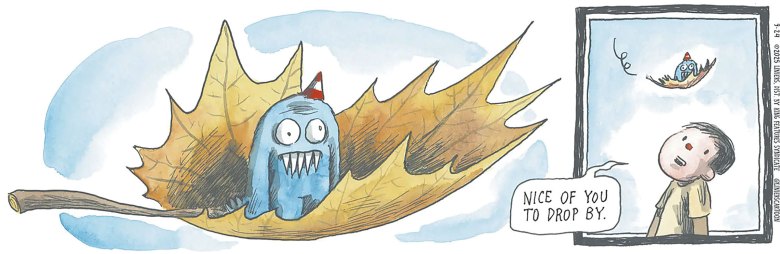

While other widely syndicated cartoons take place in narrowly constructed worlds populated by a few major characters — say, “Cathy,” which is about the crises of a middle-aged woman, or “Garfield,” about an abusive, gluttonous cat — “Macanudo” is a universe of strange multitudes. It’s populated by lesbian witches, gay elves and existential penguins; a precocious little girl named Henrietta ponders the meaning of life with her cat, Fellini; there’s a blue monster named Olga, who can only say her own name.

The humor of “Macanudo” ranges from the philosophical (Henrietta strolls through the woods with Fellini and muses: “I don’t understand why I’m feeling nostalgic. I’m still kinda new.”) to the meta (A penguin announces to several other penguins: “We are just a collection of scribbles!”) to the surreal (elves in extremely tall hats, doing anything). In one strip, a little girl, tucked into bed, complains that she’s slightly cold. Her cat jumps on top of her, and then she’s cozy. That’s the punchline: She’s cozy.

“I don’t know what people expect from a daily strip. I don’t know how other people think. I don’t know what they think is funny or not funny,” Liniers told me on a visit to his house last month. “I just do this for myself.”

The Penguin Guy

Liniers came to Vermont more or less on a whim. Before he and del Campo had kids, they’d spent a year in Montréal on an artist exchange, and they thought it would be fun for their daughters to live in a place where it snowed. So Liniers applied for a fellowship at the Center for Cartoon Studies in White River Junction, in spite of the fact, as he put it, that he “didn’t know what a ‘Vermont’ was.”

Likewise, Sturm had never heard of the Argentine cartoonist, whose work wasn’t yet syndicated in the U.S. But he quickly developed a deep admiration for Liniers, both as an artist and a person.

“He’s charismatic and fun and an utter delight to be around, and that alone is rare,” Sturm said. “And his facility for drawing is exceptional. Each panel has a freshness to it, and every line feels like it’s carbonated and alive.”

“There’s a psychedelic quality to his work that I absolutely love.”

Harry Bliss

When Liniers and his family arrived in Norwich, they figured they would stay for a couple years, then move back to Buenos Aires, where Liniers had spent his whole life. They were wrong. “It was way too pretty,” Liniers said. His daughters, ages 11, 15 and 17, have now spent most of their lives here.

Liniers may still be lesser known in the U.S. than in Latin America, but his work is highly respected by fellow cartoonists. “I don’t know what his drug intake is, but there’s a psychedelic quality to his work that I absolutely love,” said New Yorker cartoonist Harry Bliss, who lives in Burlington and Cornish, N.H.

In addition to producing “Macanudo,” Liniers has drawn half a dozen covers for the New Yorker. His books for young readers include Good Night, Planet, which won an Eisner Award, cartooning’s most prestigious honor, in 2018. His most recent children’s book, The Ghost of Wreckers Cove, coauthored with del Campo, came out in September; together, the couple also run an imprint called Editorial Común, which publishes graphic novels in Argentina.

But the daily strip is still Liniers’ main creative project, often superseding other worldly concerns. When I met him recently at his Norwich home in the middle of the day, I found him at his desk, still wearing a mismatched set of plaid flannel pajamas. He greeted me with unselfconscious warmth, then excused himself to change.

Liniers, 51, has thick, square-rimmed glasses and scruffy salt-and-pepper hair that appears to enjoy considerable free will. In conversation, he’s prone to invoking highbrow and lowbrow cultural references in the span of a single thought — James Joyce to R2D2 and back again — with a sort of unpretentious affection, as though they’d all just been hanging out on a stoop. As a kid, Liniers was painfully shy, and making comics helped him channel that awkwardness into a vulnerability that resonates with others. “When I started publishing the strip, it was like sending soldiers ahead of me, an advance guard that lets people know who I am,” he said. “I am the penguin guy.”

When I arrived, he’d been working feverishly to complete a stockpile of strips before leaving for a three-and-a-half-week tour across Europe with his friend Kevin Johansen, an Argentine American musician with whom Liniers occasionally performs. Johansen plays guitar and sings, and Liniers sits at a desk onstage and draws while a projector displays his work on a giant screen. Sometimes, the two men switch roles — Johansen draws, and Liniers plays guitar — the effect of which Liniers likens to putting a normal guy in an Olympic track meet. “You have no idea how good those people are until you see an average person try to do what they’re doing,” he said.

Producing a daily strip requires both discipline and equanimity. “Daily cartoonists can draw their asses off, because they have to,” said Bliss, who’s drawn his own daily comic, “Bliss,” for two decades. “It’s not this thing where you submit once a week to the New Yorker, and they buy one or they don’t,” he said. “You’re doing it every single moment, every day. It trains your brain in a very specific way, and you just get better.” For Liniers, being afraid of filling a blank page would be like being afraid of brushing his teeth.

Nor does Liniers worry about running out of ideas, because no idea is too big or too small for his strip. The only bad cartoon, in his estimation, is one in which he fails to delight or surprise himself. “When I started the strip, I figured nobody was reading it anyway,” Liniers said. “So I made it into something where everything I can think of, I can do.”

A Vibrant Mess

When graphic novelist Emma Hunsinger was a student at the Center for Cartoon Studies, from 2018 to 2020, she would babysit Liniers’ and del Campo’s daughters. After she had put the girls to bed, she would sometimes peek into Liniers’ home office — at the time, a room hardly bigger than a closet.

“It was absolutely trashed,” said Hunsinger, who lives down the road from Liniers in Norwich with her wife, Vermont cartoonist laureate Tillie Walden. “It was hilarious. There was shit everywhere, but mostly, it was drawings — like, finished strips that were in newspapers, circulating all around the world, just piled up all over the place. It was such a mess, but these vibrant, beautiful cartoons were the mess.”

“That’s why I go to art: to live more lives than the one I’ve been given.”

Liniers

This mess helped Hunsinger understand something fundamental about Liniers: His need to create is so inborn, and so overwhelming, that he will find a way to do it under any circumstances.

“Some cartoonists are so precious about their work and their materials,” Hunsinger continued. “They’re like, ‘I need this special nib that was carved out of a reindeer’s antler,’ or whatever. Ricardo makes his comics with a uniball roller pen that you can buy at Staples for, like, $20 a pack.”

Liniers has since moved his desk into a small room off the kitchen. The wild profusion of sketches and finished drawings, which seem to grow upon his desktop the way mushrooms grow on a log, has moved along with it.

Printed matter, in general, occupies a considerable proportion of the surface area inside the house. An entire wall in the foyer, at least eight feet high and twice as long, has been consecrated to floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. To get to the part of the house where Liniers works, you have to pass through a door disguised as part of the bookshelf wall.

Growing up, Liniers read omnivorously — Star Wars comics, classics of Western literature and, at perhaps the too-tender age of 11, Stephen King’s Pet Semetary. “I’m all for tiny trauma,” he said. “That’s why I go to art: to live more lives than the one I’ve been given.”

When Liniers was 12, his cousin loaned him a collected volume of the Argentine cartoonist Héctor Germán Oesterheld’s “The Eternaut,” a serialized strip about an everyman turned resistance hero who battles alien invaders. “It was the coolest thing I’d ever read,” he said. (This year, “The Eternaut” was adapted into a Netflix series.)

Liniers was born in Buenos Aires in 1973, the beginning of the darkest 10-year period in Argentina’s history. A military junta, aided by the U.S. government, oversaw the kidnapping and execution of an estimated 20,000 to 30,000 people — students, writers, artists and political dissidents, most of whom vanished without a trace. Among those was Oesterheld, along with three of his daughters.

By the time Liniers read “The Eternaut,” Argentina’s defeat in the Falklands War and economic turmoil had led to the collapse of the junta, and a democratic government had been elected. No one in Liniers’ family was targeted during the military’s campaign of domestic terrorism, but when he learned about the fate of “The Eternaut” creator, the brutalities of the dictatorship became personal for him. “Suddenly, the dictatorship took the form of someone I felt I knew,” he said.

In spite of this dark backdrop, Liniers speaks fondly of his childhood, a paradox that is also the essence of “Macanudo”: Everything can be bad and great at the same time. His parents took him to Disneyland and the movies, and they encouraged his love of art and books. Liniers said Johansen, his musician friend, sometimes jokes that he can tell Liniers has had a good life, because he can listen to two Radiohead albums in a row and not fall to pieces.

Feeding Creativity

Liniers’ path to cartooning included several false starts. He tried studying law, like his father, which he quickly abandoned due to boredom. Then he considered working in advertising, but that didn’t take, either. In his early twenties, he realized that he already knew what he loved to do, and he would lose his mind if he didn’t do it.

“That was my RoboCop moment, when the thing turns red and starts beeping like crazy,” Liniers said. “I told my parents that they were going to have to feed me for 20 more years.”

Liniers has been drawing for as long as he can remember, but he never had any kind of formal art training. One day, he saw a flyer for a cartooning workshop and called the number in a panic, convinced he’d never get a spot. As it turned out, he was the only person who signed up for the class. Liniers is now the godfather of the instructor’s children.

For a few years, Liniers drew a weekly strip called “Bonjour!,” which he describes, pejoratively, as “weird.” It was dark and occasionally overwrought — “It was me pretending to be punk,” he explained — though certain motifs (existentialism, penguins) would persist in “Macanudo.”

Then, in 2002, he got a lucky break. A fellow cartoonist told him that La Nacion, one of Argentina’s biggest daily newspapers, was dropping “Zits,” because the humor (snow, basketball) was too culturally specific to the U.S. She put in a word for Liniers, and he got the slot, at the modest rate of $200 a week. When he received complaints that there weren’t enough punchlines in the strip, he drew strips that mocked the very idea of a punchline.

After Liniers published a graphic novel for young readers with Toon Books, a children’s book imprint founded by Françoise Mouly, art editor for the New Yorker, Mouly asked him to draw covers for the magazine. Since 2014, Liniers has illustrated half a dozen. Compared to the more simplified visual language of his cartoons, Liniers covers’ for the New Yorker are richly detailed, showcasing his playfully serious lines. Instead of cross-hatching, a technique of layering lines in opposite directions to create contours and shading, Liniers tends to shade with lines that all go in the same direction, lending a scratchy, lo-fi quality to even his most elaborate scenes.

“Hipster Stole,” from 2015, depicts a couple out for a stroll around the neighborhood, dressed as though they’ve just raided the closet of a 19th-century lighthouse keeper. The man’s beard, the eponymous stole, wraps around them both in a sort of Duchampian scarf, its hairy density suggested by a thatch of pen strokes.

Liniers told me it never occurred to him that he might draw covers for the New Yorker. Like the rest of his career, he said, it happened improbably. “My fantasy was to make it to Uruguay,” Liniers said, “so I could say the strip was international.”

It’s the Little Things

Since moving to Norwich, Liniers has largely managed to avoid traditional employment. He taught a class on Latin American comics at Dartmouth College in Hanover, N.H., for a couple semesters — “I’m sure the parents of my students were super happy about that,” he said sarcastically — and he gives occasional lectures at the Center for Cartoon Studies. But mostly he’s at home, happily scribbling.

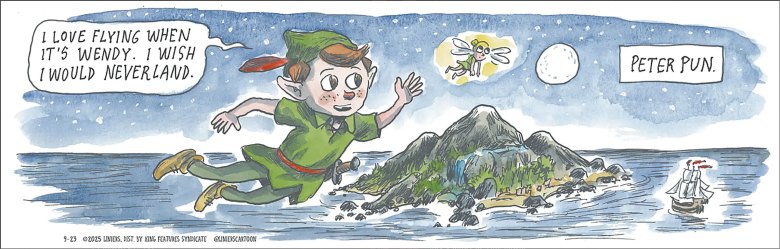

Liniers typically draws his strip in the morning, “when you’re still confused from that David Lynch movie in your head from the night before,” as he put it. He does one drawing for both English- and Spanish-language publication; if the humor doesn’t translate from one language to the other, he comes up with a version of the script that works with the same drawing. Recently, he drew a character called “Peter Pun,” a spoof on Peter Pan, but there is no Spanish equivalent to “pun” that rhymes with “Pan.” So he wrote an English strip about Peter Pun, a naïf who loves wordplay, and a Spanish strip about Peter Flan, a naïf who loves dessert.

Over more than two decades of drawing “Macanudo,” Liniers has learned that not everything can be a masterpiece, nor should creating masterpieces be the point. “Some days, you’re smart, and some days you draw a whale, and you look at the whale, and the whale looks back, and it’s just despair,” Liniers said. “I feel like Ahab. But you still have to publish, because the days keep on coming.”

Sometimes, he tries to keep his cartoons simple so he can attend to other things, like preparing to leave the country for almost a month. Other times, he can’t help himself.

Liniers showed me two strips he’d been working on in his sketchbook — one depicting two penguins in the tundra, the desolation of which he had evoked with nothing more than an unbroken horizon line, a few squiggles and white space; the other, an exquisitely detailed forest scene featuring a girl and a cat on a footbridge over a roaring brook.

What makes Liniers’ work singular, said Sturm, director of CCS, is its combination of spontaneity and precision. “He allows his line to wander and play, but he’s also in total control of it,” Sturm said. Even his simplest cartoons have an emotional landscape.

This quality is a function not only of his ability to manipulate scale and perspective but also of how he uses silence. In one four-panel illustration, Henrietta, the little girl, is reading in bed with Fellini the cat and Mandelbaum, a teddy bear. The first panel shows her cozily ensconced with her book and her furry friends, with no dialogue. In the second panel, she looks up from her book and says to the cat, who is now looking at her, “I don’t know about my life being an open book.” In the next panel, still addressing the cat, she says, “But I intend to make opening books my life.” The fourth panel shows her quietly reading again.

Other cartoonists might have left out the first and last panels, which don’t seem to advance the plot. But as New Yorker cartoonist Bliss explained, those silent bookends are doing the heavy lifting. “They’re creating resonance,” Bliss said. “The little girl has had a eureka moment, and those two textless panels allow the reader to digest it. It’s kind of sublime, actually.”

To the extent that “Macanudo” has a summarizable unifying premise, it’s these kinds of small epiphanies. “I’m the journalist of the tiny thing,” Liniers said. “The smell of a freshly sharpened pencil — that’s my news.” The saddest strip he ever made, he said, was about a father picking up his kid who has fallen asleep in front of the television. As the father carries his son to bed, he strains his back. The text reads: “The last day your father picked you up.”

Liniers chronicles the little joys, too: The first panel of a strip featuring La Guadalupe, a Day of the Dead-esque character who wears a black cape and a pointy hat adorned with flowers, shows her ogling much bigger flowers. She touches the small flowers on her hat, looking forlorn; in the next panel, she’s walking away jauntily, sporting a crown of huge blooms. With no text and the tiniest of pen strokes, Liniers captures this subtle emotional trajectory — from shy covetousness to vague disappointment to private satisfaction — on La Guadalupe’s skeleton face.

Given the current political climate in the U.S. — in particular, the threats to foreign citizens by the Trump administration — and the fact that he’s here on a green card, Liniers has been more careful about what he says in his strip and on the record, a caution he deplores. “Self-censorship is the first sign of absolutism, and it’s scary,” he said.

But “Macanudo” is rarely overtly political, and Liniers isn’t interested in making topical art about the machinations of power. He’s more concerned with how life goes on amid the upheavals. “The big thing is horrifying, but my life is not there. My life is the small life,” he said. “I can have a glass of beer with my friends. My parents are really nice. I can smell the pencil shavings. It’s bananas how much we’re all living the same life, the way we fall in love and the way we screw up and the way we triumph.”

This might seem like a shockingly optimistic outlook for someone whose life began under a military dictatorship. But in another sense, it’s deeply real.

After President Donald Trump was elected in 2016, Sturm said, a bunch of people from the cartoon school, including Liniers, got together to process their feelings. Some hadn’t slept in days, but Sturm was struck by how sanguine Liniers seemed.

“I remember thinking, He’s been there and done that. He’s lived through authoritarianism and rightward turns,” Sturm said. “And there he was, smiling. His creative life force warmed that room.”

Hunsinger told me that she was walking in downtown Hanover recently and noticed a suspiciously beautiful flyer. Upon closer inspection, it turned out to be a Liniers original — an advertisement for his daughter’s upcoming show at Sawtooth Kitchen, a restaurant and nightclub. “It clearly wasn’t a toilsome drawing, but he still made it really eye-catching,” she said. “He might be a global artist, but he can still bust out a flyer for his daughter’s band’s gig at the chicken place.”

In fact, he doesn’t seem to need any audience for his art. Among the hundreds of books on his foyer shelves is a collection of some of Liniers’ favorites — Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse, the complete works of Franz Kafka, James Joyce’s Ulysses — covered in his hand-drawn and watercolored dust jackets. Over the years, he’s made about 60 of these, and each one is a meticulous work of art, the sort of project in which you could imagine Liniers losing himself for an entire afternoon. Most people will never see them.

The original print version of this article was headlined “Great and small | Argentine cartoonist and Upper Valley resident Liniers turns ordinary life into extraordinary comics”

The post Liniers Turns Ordinary Life Into Extraordinary Comics appeared first on Seven Days.